the kill was beautiful.

on horror, the body as a vessel, & the missing raw desire of the modern scary movie.

someone once told me i write like i’m bleeding. it’s no wonder i’ve fallen deeply for the terrible.

My reader summary on Fable reads as the following: “Thriving on a mix of gothic allure, dark academia, and the glamor of forgotten Hollywood, you're one candlelit room away from starting your own cult of book lovers! Beware of any book clubs you might create!”

A cult, I muse—maybe that would be something.

October ignites a particular hunger in me, a taste for something wet and warm. I’m a modern vampire without the fangs, craving a league of horror. I want a million final girls left standing. My Letterboxd diary is bloodstained for the month, filled with horror lists, both vintage and new. This year’s niche? Lesbian vampires circa 1960-1980.

The deeper I go into the month, the darker the movies become. I start with something light, trashy, a bit of fun with campy characters tripping over thin air, something to make me say, What the fuck? with an airy laugh. But soon, the thirst starts to claw its way up. She—the one I’ve buried—rises from her grave and begins to whisper, pleading for a little more blood, a bit more skin, another layer of manipulation. Just more.

By October 23rd, my chest feels like a revolving door, my Scorpio heart beating with a seductive fever. I used to shy away from the typical Scorpio narrative: sexual desperation, manipulation, secrecy, intensity. I was the “good girl,” Catholic-raised, Catholic-schoolgoer (read: survivor), as sweet as you please.

But that’s never been the truth, has it?

Scorpio rules the reproductive organs, genitals, the primal pulse. I consider these all very animal parts of us. It’s not an insult—I’m at home with it. I've always felt more animalistic than feminine. People just get confused.

In her beautiful piece on body horror,

writes,“Before the concept of being desirable came to fruition in my mind, I was known to act like an animal during adolescent play.”

This ricocheted through me. I was the same as a young girl. Whenever I played pretend, I was always surviving something.

I would go as far as I could without being too uncomfortably distanced from home and perform the whole bit: running as deep into the woods as I could, staging one-woman scenes of breathless terror, hands trembling, a voice fractured by imaginary threats. I still run for pleasure when I’m home, blood thrumming in my legs until my skin feels taut and itchy.

My life was exciting then. Everything felt alive. I was the prey, pursued by someone or something that wanted me so deeply it didn’t know how to stop itself. It didn’t know what else to want other than to snuff me out.

Per the words of

: Fighting, clearing energy is good.Yesterday, on a three-hour call, someone told me I didn’t seem the type to want a submissive partner. I smiled, all teeth, and admitted that I get that a lot. Maybe I seem soft and thin, a piece of cotton candy. I don’t mind; it’s a good lure.

And some part of that “sweet” truth still holds—I value kindness, and I work hard to be good. But there’s another side, the one that resents giving up control. And I can be so mean.

When I faked that survival, those desperate escapes, I was clearing that energy, finding a release.

I don’t remember the first time I watched a horror film. I just know it emptied me out. It purified all that frenetic energy.

Nearly every woman I know has a love affair with horrific media, a fascination that borders on ritual. Many of us crave the vampiric allure, and I’m no exception. But there’s something about a good slasher that draws me in, even if it occasionally makes me worry about myself.

Of course, I have limits. Take the Terrifier franchise—a gruesome plunge into torture porn that only leaves me feeling queasy. Lately, it seems too many horror movies fall under that bleak umbrella. Perhaps, I suspect, it’s because we no longer know how to utilize sex and intimacy within them.

What made Scream (1996) so captivating—and spurred legions of Ghostface fanfiction—was its restrained, erotic tension. Objectively, the story is nightmarish: your boyfriend and his best friend slaughtering everyone you know and planning to kill you, and guess what? They get off on it.

Yet, Craven didn’t romanticize it; he crafted something that pulsed with dark intimacy, a perverse undercurrent. Billy’s grip on her neck, the blood smudged across his face, his intense, singular focus on her in what should have been their moment (that night was supposed to be The Night if I remember correctly)—that was cinema.

There’s a magnetism that comes with someone loving you, lusting over you, and warring with that while intending to harm you. There’s a primal call from the blend of lust and violence, of love intertwining with danger.

Nature itself reflects it: A praying mantis eats her mate when bored; a victorious female in a fight with a male will cannibalize him. The black widow does the same. The female scorpion (ha!) exacts the same ritual.

Few directors manage to capture this in a way that resonates, yet Nicolas Winding Refn accomplishes it masterfully.

The Neon Demon (2016) is one of my favorites, a film dripping with jealousy, hunger, and twisted admiration—particularly potent as it plays out between women. Again, we come back to that perverse cannibalization.

Fellow models Ruby, Gigi, and Sarah (spoiler!) slaughter and consume Jesse, their jealousy over her beauty festering until they’re driven to devour her. And then, after all that—she wins; they throw her up (her eye, actually) like an unwanted offering. It’s a divisive film, but the ones who understand really understand.

What I find so seductive about The Neon Demon—and what many viewers seem to overlook—is that the girls’ resentment is tinged with lust. Jesse, as the Neon Demon, is a manifestation of their desires and ambitions—a dark reflection of what they would do to hold onto beauty and relevance.

In one of the most stunning pieces I’ve read,

writes,“Upon birth, every girl is entered into a competition: become the most beautiful woman to ever live, then never die.”

The girls’ envy drives them to the ultimate form of intimacy, a baptism in Jesse’s blood, taking her essence into themselves. To desire and hate someone so profoundly that you submerge your naked body flush in their blood—that’s a darkly erotic image.

I miss that rawness in horror, that willingness to use the body as a vessel for desire without the sin of objectification looming over every scene. Somewhere along the line, we forgot that intimacy, not mere brutality, is what gives horror its depth.

Stoker (2013) and Crimson Peak (2015)—both starring Mia Wasikowska, a fellow Scorpio with an earth moon—lean gothic rather than outright horror, yet they’re beautiful meditations on the subtle, twisted erotic.

In Stoker, Wasikowska’s character, India, is a coldly sociopathic young woman who shares a strange “connection” with her uncle, Charlie. Now, to be clear, I’m not here advocating for incest (yes, I see you eyeing my ASOIAF and HOTD obsession), but one of the most bafflingly sensual and batshit insane scenes in the film comes when Charlie murders her date in a brutal fit of jealous protectiveness.

The aftermath finds India in the shower, and here’s where it gets masterful.

At first, the sound design suggests she’s crying; the quiet, choked sounds are reminiscent of the suppressed sobs of someone hiding their tears in the dark. But as the camera continues to lower, aching to hold her in its view, it reveals the truth—India is pleasuring herself, entirely aroused by the murder she just witnessed. It’s dark, and yet impossible to look away from.

It’s still one of my favorite scenes, partly because of the emotional misdirection.

Prior to this, I convinced myself that the underlying sexual nature of Charlie and India was just a flight of fantasy, that I was meant to be focusing on her mother and him instead. I told myself India was traumatized by his villainy, not…enraptured. But no—she saw him as perfect, as darkly beautiful in his violence, a kind of perfection that pushed her over the edge.

The film had been setting up this intimacy all along through things we would ordinarily find unsettling. The piano scene, with him pressed close to her back; sending her to the freezer to find a body, gambling that they were set from the same cloth; the “designer” shoes that kept appearing as gifts.

(Side note: I’ll admit, the shoes would’ve gotten to me too. There’s something lushly sensual in the slight reveal of an ankle, leg, or neck in period pieces. I once saw a vampire bite into someone’s ankle on TV, and…let’s just say the Victorian women were onto something.)

Watching, I felt a jolt of horror mingled with something electric, my mouth rounding into a perfect little o, my hand almost rising to cover it as if to suppress the building thrill in my chest.

Five stars, easily.

Similarly, Crimson Peak, directed by Guillermo del Toro, is layered with sensual dread, a decadent romance wrapped in blood.

Edith, our heroine, arrives at the decaying mansion, where she becomes ensnared in a sinister love triangle with her new husband, Thomas, and his sister, Lucille. Thomas’s affection is tender, almost fragile, and contrasts with Lucille’s relentless possessiveness.

The movie doesn’t need to shock us with graphic displays; it unsettles us instead with the intimacy of each gaze, each careful touch. The sensuality isn’t in anything explicit but in how love itself becomes the shackle. We fear Lucille not because she is violent but because she loves in a way that refuses to let go.

Del Toro taps into something chilling here—how far our most vulnerable emotions will go to bind and trap us, turning into something claustrophobic.

As Tumblr user thegirlinyourmemories put it, “Love guides me but also traps me.”

Crimson Peak embodies this perfectly. Edith’s romantic yearning leads her to Thomas, but it’s that same yearning that traps her in the twisted labyrinth of Allerdale Hall, haunted by the ghosts of Thomas’s past. The horror here is intimate; it’s in the fear of being known too completely and desiring something enough to stay.

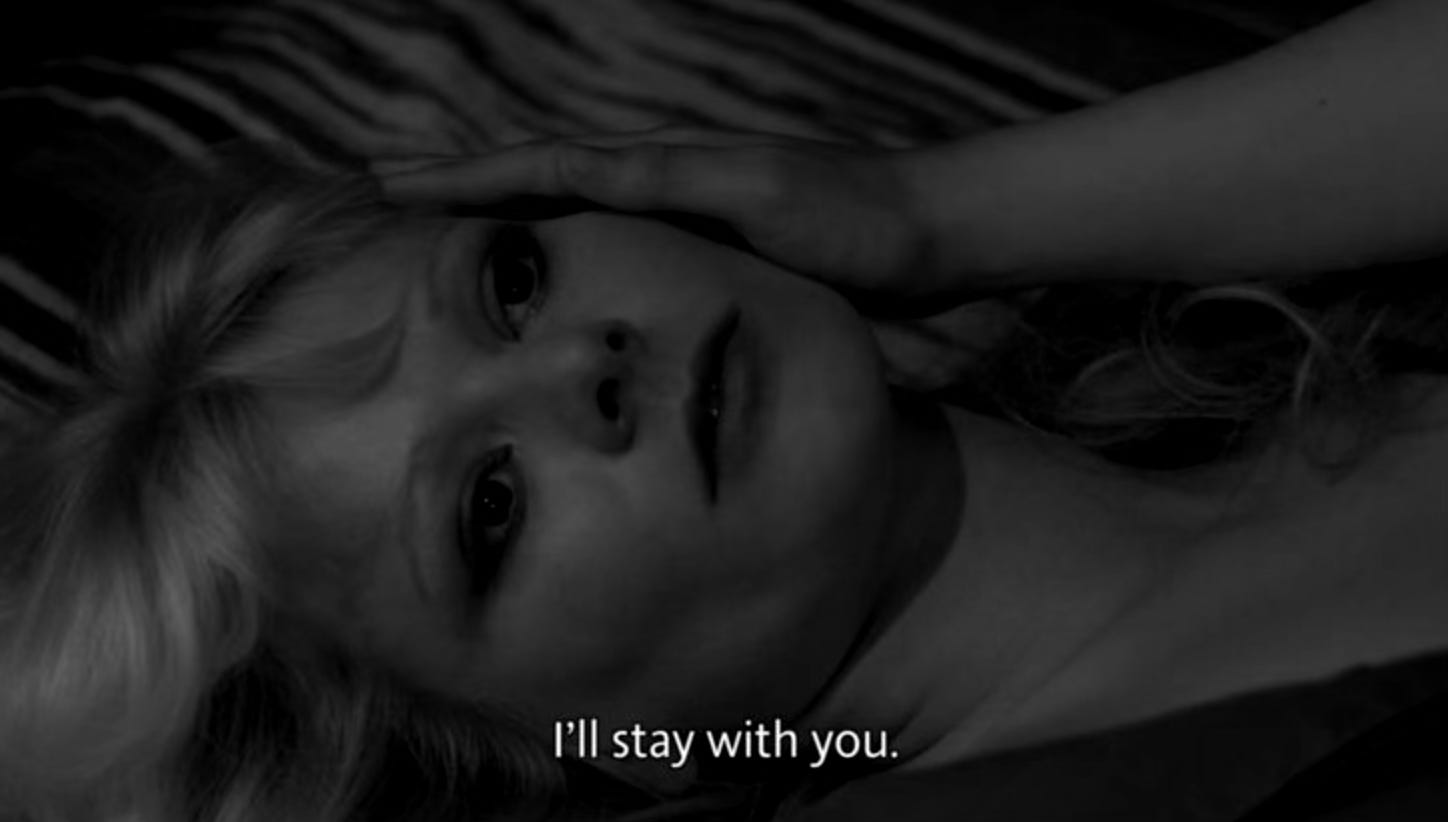

Then, there’s The Living Dead Girl.

Jean Rollin’s 1982 film introduces Catherine, a woman resurrected from the dead who yearns for blood. But this isn’t the carnage-soaked massacre of modern slashers. Rollin’s touch is restrained, exploring instead the terror of love that outlives death.

Catherine’s relationship with her childhood friend Hélène unfolds as a brutal ballet of need, devotion, and corruption, as Hélène tries to protect her even as Catherine’s vampiric thirst consumes her. The Living Dead Girl feels almost like a lament for the bond between them, corrupted by an intimacy that became too close, too absolute.

There’s horror in Catherine’s need, in the way Hélène’s love traps her, forcing her to make sacrifices even as she knows she cannot save Catherine. Rollin’s film is devastating in its tenderness—it doesn’t need to be graphic to disturb us. Instead, it unsettles us with the soft, sickening grief of two women bound by a love that has defied death but come at a terrible cost. Catherine’s beauty, her bloodlust, and Hélène’s devotion all circle each other, spiraling toward a dark, tragic inevitability.

There’s a void in horror lately, a hollow place where intimacy once lurked in shadow, where touch was as horrifying as any blade. Crimson Peak, The Living Dead Girl (1982), and all the other films mentioned stand as a testament to how horror can—and should—lure audiences with a mix of dread and desire, blurring them until they’re inseparable.

These films explore the deep unease of needing something or someone so intensely that it becomes monstrous, of “adoration” so extreme it feels necrotic. Sensuality and intimacy aren’t decorations—they’re integral to the scare. And when we look at horror’s modern playing field, what we’re often missing is this interplay of love and fear, of desire and doom.

Many recent films seem unsure of how to use the body without complete desecration. But true horror doesn’t need to exploit; it needs to expose. It’s not in the gore but in the connection, the quiet implication that love, as beautiful as it is, can be just as dangerous as death.

And off-screen, that’s precisely where the real fear lies.

I love you forever. We’d kill for that.

what a beautiful blend of the seasonal spooky with the eternal primal desire for love, glad to have come across you!

horror is actually probably my least favorite genre 🫣 I've gotten more into it in the past few years, but I'm still *very* picky when it comes to the genre lol. I def do agree that there's a different vibe to more recent horror films and this is an interesting explanation of why.

also if you haven't seen Byzantium, I think you'd really be into it. it's more of a mystery/thriller than outright horror, but it's my favorite vampire film and Gemma Arterton is so 😵💫😵💫😳😳 (tw for rape tho, not shown onscreen but it is very clear what's about to happen)